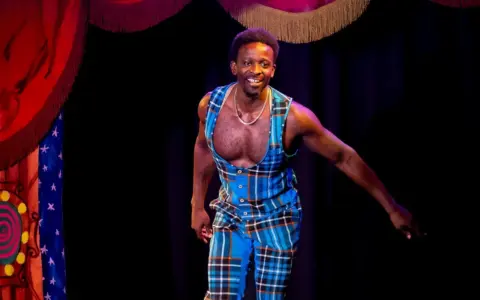

Asexual Bangladeshi artist Dipa-Mahbuba-Yasmin shares beautiful art with tragic circumstances at Canberra’s SpringOUT Festival.

The title of your talk at the Shine Dome on Tuesday is ‘When Speech is Forced Down, Art Must Speak’. Could you tell our readers a bit about your background and why that statement resonates with you?

That phrase comes from one of my own curatorial statements—it was also the title of a group exhibition I curated in the UK in 2022. But its story began long before that. In 2016, two Pride activists in Bangladesh were brutally murdered by Islamic extremists. Their deaths sent shockwaves through our community. People grew terrified, went into hiding and began using pseudonyms to stay safe.

But how long can one live in fear and silence?

Out of that darkness, we created Bangladesh’s first queer art gallery—a space where anyone, no matter what they painted, could simply be. When our voices were silenced, art became our alternative language. Each brushstroke was an act of courage. And since we have no gay bars or safe public spaces, that small gallery became our gathering place, our refuge, our lighthouse.

As an asexual person, you’ve said you are “not allowed to not have sex in Bangladesh.” Could you share what that feels like?

In Bangladesh, sex is seen as a taboo and a sin—yet not having sex is viewed as an even greater one.

If a man says he doesn’t desire sex, people mock him relentlessly. They call him broken, they bully him—at home, among friends, at school, at work—everywhere. For a woman, it’s even worse. If she is unmarried, people say, “Just get her married, and everything will be fine.” If she still refuses sex after marriage, she can be forced—because marital rape is still legal in Bangladesh.

Under Sharia law, many believe that if a wife refuses sex, her husband has the right to ‘punish’ her. So, in this culture, choosing not to have sex is simply not allowed—for anyone. As an asexual person, it feels like existing outside the rules of your own body, your own freedom. You are constantly made to feel unnatural for simply being yourself.

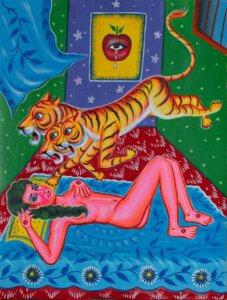

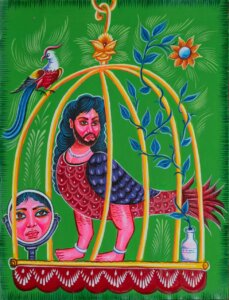

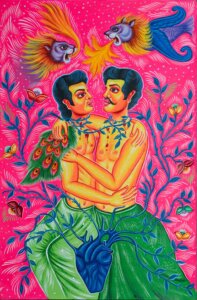

Your artworks are full of color and life, yet they tell stories of unimaginable pain and struggle faced by LGBTIQA+ people in Bangladesh—realities that may be hard for some queer Australians to imagine. As a ‘queer aesthetic activist’, how do you balance beauty and resistance in your work?

Also, could you explain what ‘folk art’ means and how you collaborate with folk artists to create your pieces?

In Bangladesh, protest is dangerous. We cannot march on the streets, we cannot speak openly in the media. So our art became our protest. Aesthetic activism was not a choice—it was the only way left for us to breathe.

Many of my paintings are visual stories—illustrations of real cases we’ve documented through our queer helpline. These are the lives the mainstream media refuses to see. I often use rickshaw art—a bold, colorful form of Bangladeshi folk art—to capture attention quickly and speak in a visual language that people already love and understand.

Through those bright images, I challenge traditional moral binaries and slip queer narratives into familiar forms. It’s a delicate dance between resistance and recognition—telling radical stories through colors that feel like home.

Could you tell us a bit about the range of artworks that will be on display at the Shine Dome on Tuesday?

When I left Bangladesh for Australia, it was a sudden, life-changing decision. I could not bring much with me—but I carried 40 queer paintings, each one a fragment of my journey and my community’s story.

I entrusted all of them to the A.C.T. Asexuals collective, and many will be available for sale, with up to 60% of proceeds going to support displaced queer people. The Shine Dome exhibition will be their public debut in Canberra—an artistic homecoming for me, and an introduction of our voices to this new land.

Which artists and activists inspire you and what message would you like to leave our readers about human rights?

I’m deeply moved by artists who push the limits of their mediums to speak for their nations and communities.

Queer artist Chitra Ganesh, queer ceramic artist Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and puppet artist Saba Niknam have all inspired my work in profound ways. They remind me that creativity itself can be a form of rebellion.

As for human rights—especially for queer people living under hostility and fear—I want to say this: Don’t let the borders of maps or families define your world. Reach beyond them. Speak, connect and keep faith in your global queer family. Even when your homeland rejects you, your rainbow family will always hold space for you.

-Danny Corvini